What Makes Grand Cru Great

Grand cru is usually translated to "great growth", though the long-winded "(product of) a great growing site" gives a clearer understanding of the meaning. Cru is the past participle of the verb croître, to grow. However, what this term means in practice in the French wine industry varies by region.

Burgundy

Grand cru Burgundy is much the most written-about level of Burgundy (and most searched-for on our website), even though it only accounts for less than two percent of production.

It is probably the first region people think of when hearing the term "grand cru", and possibly the easiest to understand as a classification, even if many wine professionals spend entire careers getting to grips with the subtleties. Today, every vineyard in the region is part of a hierarchy that runs from grand cru through premier cru and village wine to generic Bourgogne.

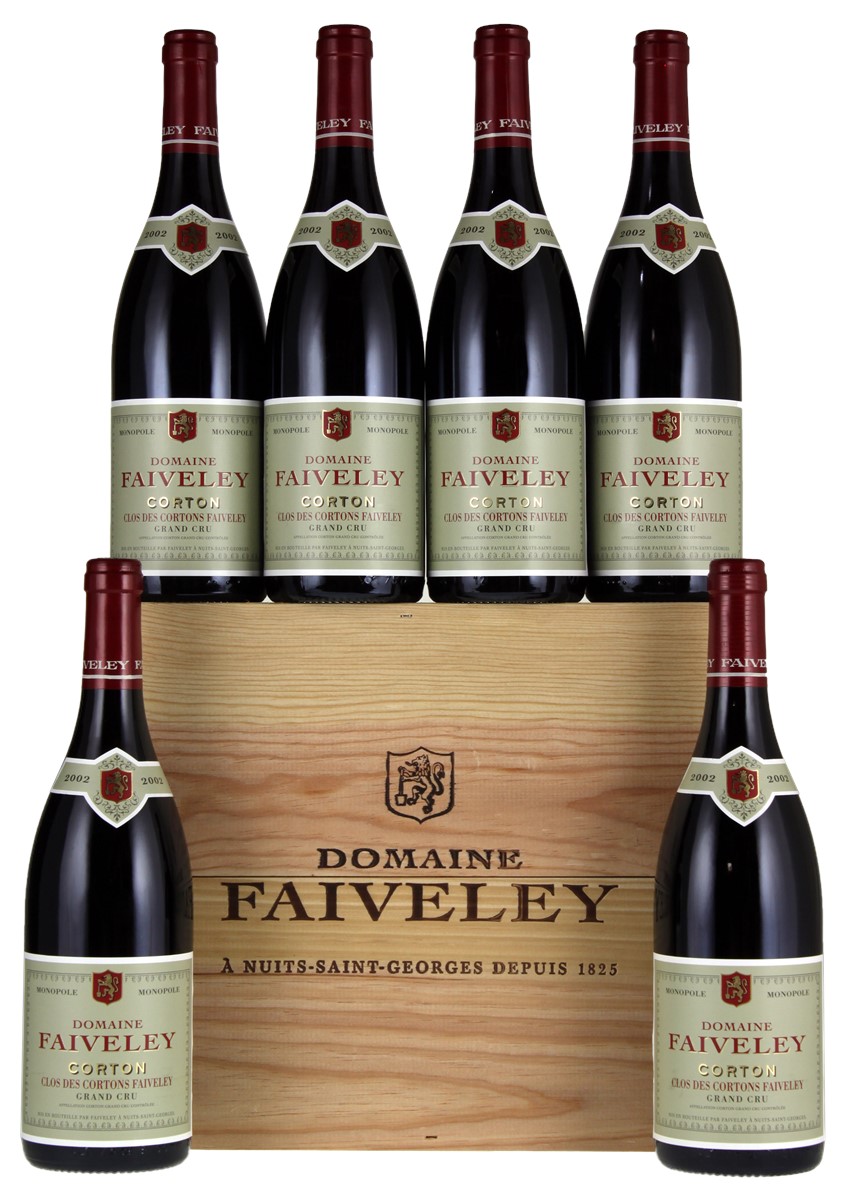

There are 31 grand cru vineyards, supplying 33 grand cru appellations (counting Corton as one site with the overlapping Corton, Corton-Charlemagne and Charlemagne appellations, and excluding Grand Cru Chablis). These sites range from 0.84 hectares (2.1 acres; La Romanée – a monopole of Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair and the smallest appellation in the world) to Corton at 97.5ha (241 acres). The majority lie in the range of 5-17ha, but size is not a uniform aspect of this designation of quality.

Unlike Chablis, each grand cru vineyard is an appellation in its own right. Because of this, the vineyard name is usually the most prominent element of a label and – annoyingly for most of us – there is no sure-fire indication on the front label as to which village(s) the grand cru is located in.

The roots of the Burgundy classification system go far back to the Cistercian monks, who split from the Benedictine order in 1098 to embrace a more pious, austere life, concentrating on hands-on farming over and above property ownership. While Benedictines had developed vineyards for several centuries, the delineation of their vineyards is thought to have been more concerned with ownership, while the Cistercians are credited with identifying the best plots in terms of the wines they produced.

In 1855, the same year as the better-known Bordeaux Classification, Dr Jules Lavalle published his famed Plan Topographique of Burgundy's Côte d'Or, a detailed map of all the vineyards from Dijon to Santenay. But, though this work forms the basis for the 400+ appellations set up in 1936, Lavalle classified the top sites as Tête de Cuvée (and below this Première, Deuxième and Troisième Cuvée). The 1855 Bordeaux classification and Lavalle's were conceived as snapshots of the then-current situation, but both have become set in stone.

However, the Burgundy appellation system dates only to 1936. From the 1800s to this point a clear distinction had developed between the production of fruit and the négociants (merchants) who sold the wine. In the 19th Century, wines in Burgundy had been classified according to the average price that wine from each – more broadly defined – area fetched, as wines were sold by négociants with no mention of individual producers. The debate over brand vs terroir developed in the early 20th Century; the 1936 appellation marked an increasing concern among more powerful growers that their product was being debased through blending with fruit from other sources.

There are six monopole grand crus but, as a result of the French Revolution and Napoleonic laws of inheritance, the other Burgundy grand cru vineyards are divided between multiple owners – nearly 80 in the case in the former Cistercian property Clos de Vougeot. Today many owners have management contracts with, or lease vines to, established domaines, but most grand cru Burgundy appellations are produced by more than one estate. In Burgundy and elsewhere, not all grand cru wines are created equal, due to winemaking differences and because, even within an 8-ha (20-acre) vineyard, soil, drainage and shade can vary, as can the age and quality of the vines.

A line-up of Chablis Grand Cru wines.© The Buyer | A line-up of Chablis Grand Cru wines.

Chablis

In contrast to the rest of Burgundy, there is one single Chablis Grand Cru appellation, and the words "Chablis Grand Cru" feature prominently on labels, along with the vineyard name. The AOC was founded in 1938 and accounts for just two percent of Chablis wines.

In contrast to all other regions mentioned here, the appellation applies to a single expanse of Chardonnay vines that sit on a southwest-facing hillside overlooking the town of Chablis, and cover a total of 100ha (247 acres). There are seven separate vineyards, called climats.

Champagne

Unlike The Côte d'Or's vineyards (or Bordeaux's wine estates), in Champagne it is whole villages that are classified as grand cru or premier cru. The system, known as the Échelle des Crus (ladder of the growths) was originally established in 1911 as a fixed pricing mechanism for the supply of grapes by growers to the Champagne houses, in response to the riots of the previous couple of years. The rating of vineyards in Champagne, as in Burgundy, has a longer, ecclesiastical history; traditionally the Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon (1638-1715) is credited with identifying better vineyards, as well as blending wines to improve the finished (usually still) product.

Grand cru villages were those that received 100 percent of the agreed maximum price for grapes for the harvest, set by a committee of producers and growers. Premier cru villages are rated from 90 to 99 receiving the equivalent percentage, while other sites receive 80 to 89 percent of the price.

Twelve villages initially received grand cru status. Five more villages were added in 1985. Today, grand cru vineyards account for less than 9 percent of the total planted area in Champagne.

Bordeaux

In Bordeaux, the term grand cru is applied differently, referring to a single château or estate, whose vineyards may consist of a contiguous plot around the main house, or – more commonly – be divided across several distinct sites.

Provence is the only other French region that has rankings (14 cru classés) based on properties.

Saint-Émilion: grand cru vs grand cru classé vs premier grand cru classé

The word "classé" (classed) is key here. Saint-Émilion Grand Cru is an appellation and could be seen as the fourth tier of Saint-Émilion wine, not the top one. In some respects, the term's significance in Saint-Émilion is closer to that of Bordeaux Supérieur or the Italian Superiore designation.

There are hundreds of wines labeled simply as Saint-Émilion Grand Cru. There is no distinct grand cru sub-zone; instead, the wines conform to more stringent AOC production rules (primarily regarding lower yields and higher alcohol levels) and pass tastings at each vintage to gain the suffix to the generic region name. But these (non-classé) wines are not included in the results of the classification of Saint-Émilion, which first took place in 1955, with revisions in 1996, 2006, and 2012.

There are now four Premier Grands Crus Classés "A", 14 Premiers Grands Crus Classés "B", and 64 Grands Crus Classés. This list cannot be changed until 2022 at the earliest. For 2012's classification, estates were given a mark based on an assessment of samples, marketplace reputation, quality of terroir, and production practices. The precise allocation of marks between these categories and the number of samples tasted varied according to whether estates were seeking premier or grand cru classé status.

Médoc, Graves and Sauternes

The best Médoc wines (plus Haut-Brion in the Graves) were organized in 1855 into a five-tier group of "Les Grands Crus Classés". Thus in this way the four (now five) top-level wines could be referred to as the Premiers Grands Crus.

However, the word "grand" is often omitted, with the individual properties tending to be referred to merely as First to Fifth Growths (Premier to Cinquième Crus), or collectively the Cru Classés or Classed Growths.

There are many caveats. Since the 1855 Bordeaux classification, many Cru Classés have bought and sold vineyard parcels without affecting their status. In contrast, Château Gloria was created and developed from 1942 onwards from parcels bought from Cru Classé neighbors but does not enjoy the same status even though, by international standards, it stopped being a newcomer decades ago and is regarded as being of sufficient quality by critics.

At more than 160 years old the system is hardly an accurate picture of current quality levels. Lynch-Bages ("only" a Fifth Growth) is an oft-quoted example of this. Lanessan (near Gruaud-Larose but just outside the borders of Saint-Julien) had a strong enough reputation then and now, but the owner in 1855 thought the classification was bureaucratic nonsense and so did not submit his wine. With the exception of Mouton-Rothschild, change in the 1855 list only happens when a property disappears such as the third growth Château Dubignon. All of this has prompted various critics and writers, and the wine exchange Liv-Ex, to publish their own rankings.

The Graves district is an outlier in the discussion of grand crus. The region introduced its own single-tier classification for red and/or white wines in 1959, with 16 properties categorized simply as Crus Classés. All of the properties lie within the newer Pessac-Léognan appellation. The top sweet wines of Sauternes were classified in 1855 as Premier and Deuxième Crus (First and Second Growths), with Yquem, picked out as a Premier Cru Supérieur.

Let's contact WeWine, our Sommeliers will introduce the best Grand Cru to you.

Sommelier Lincoln-WeWine

Source: winesearcher.com

Recommendation from WeWine

Related posts

-

-

-

-

Located in the heart of the Pauillac region, Haut-Bages Monpelou was originally under the Rothschild family, then separated in 1950, and joined Casteja family in 1970.

-

Chateau La Croix du Casse was bought by Sir Philippe Casteja in 2005, along with the Domaine de l'Eglise, representing Pomerol quality.

-

-

-

Copyright © 2020 by WeWine

You must be over 18 to consume alcohol | Sitemap